Hammer mills and mills in Grafenwöhr

Water power and wood –

these two raw materials helped the Upper Palatinate to economic prosperity in the Middle Ages. They were the basis for the extraction and processing of iron. Rich ore deposits, dense forests and powerful rivers made the Upper Palatinate the „Ruhr area of the Middle Ages“. Around Grafenwoehr, too, there are numerous testimonies to the former iron industry. Since time immemorial, water power has also been used to drive mill wheels. Hammers and mills thus alternate along the river and stream courses in the area.

Golden age in the Middle Ages

At the end of the 13th century, the iron boom had also broken out along the Haidenaab river. The hammer mills Hütten and Grub were already in operation, Gmünd followed a little later. The surrounding forests provided wood for coal piles, the coal of which was used to fuel the iron smelting furnaces. Field and family names such as Kollermühle or Meiler still refer to this today.

On small river courses and easily accessible locations, grain mills provided the most important ingredient for the main foodstuff, bread. The flourishing iron trade was, among other things, a reason for the Counts of Leuchtenberg to take possession of Grafenwoehr. There were first-class rail hammers, which produced iron rails and bars from ore, and second-class sheet hammers, which processed iron into sheet metal. Most of the hammers had considerable estates and were often noble and landed gentry, e.g. Hütten, Gmünd, Grub and Steinfels. Through the division of inheritance, new lines of hammer lords emerged, such as the Mendel family in Gmünd.

Decline in the 16th century

The flourishing of the industry resulted in the depletion of the forests. Huge amounts of wood were consumed and the forests were reforested as we know them today around Grafenwoehr. Pines grew quickly and were well suited for coal production. In the 16th century, the forests were almost depleted and the productivity of the iron industry decreased. In addition, the hammer mills in the Upper Palatinate were prohibited from making technical innovations due to regulations imposed by the Amberg hammer mills. The industry was already in deep crisis before the Thirty Years‘ War. After the war in 1648, there was a shortage of labor and ores, hammer mills lay idle, and the iron industry had become unprofitable for private hammer mills due to increasing competition from the state and from abroad. The decline of the centuries-old monostructure plunged the Upper Palatinate into great economic hardship.

New function for old hammer mills

Old factories were eventually converted, e.g. into mills that could continue to use water power or into agricultural estates. It was not until the advent of glass and mirror grinding in the 17th and 18th centuries, which also required water power as a drive, that the old hammer mills experienced a new heyday that was to last into the 20th century.

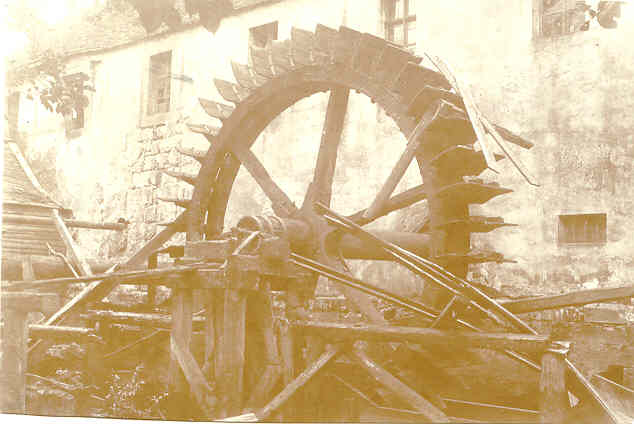

Polishing plant Hammergmünd, summer 1915

© Archive Culture and Military Museum Grafenwoehr

cycle trail ‚hammer mills & mills‘

cycle trail ‚hammer mills & mills‘